Ornament

Ornament

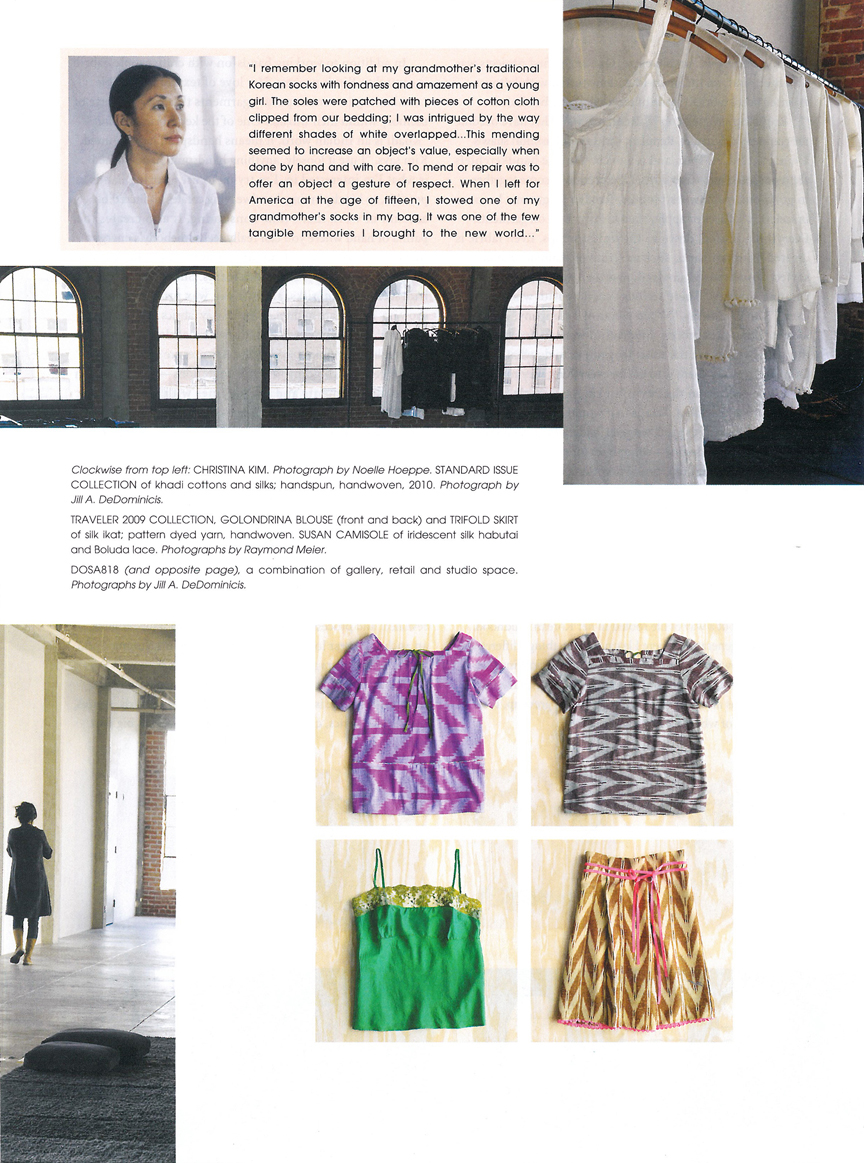

Stepping into the Dosa factory in downtown Los Angeles quickly uproots any preconceived notion about what a factory might look like. The expansive, wood-floored space feels more like something gracing the pages of an architecture magazine than a place for manufacturing global clothing, accessories and house wares line. It is what designer Christina Kim calls a "deliberately democratic" space—an open, communal kitchen, a sewing factory and showroom sharing a large, natural light-flooded space. Workers laugh and talk against the backdrop humming of sewing machines.

This concept of a democratic space mimics the way Kim structures the entire operation. There are no tangible hierarchies, and the departments can openly interact in the generous shared space. If there is any question that this is an exceptional business model, the particulars of the business prove it. Kim directly employs some thirty to thirty-five employees at any given time, with low turnaround—workers remain in this gorgeous space on average of twelve years. Roughly fifty percent of all the merchandise comes out of this picturesque Los Angeles factory. The remaining product is made in other countries, largely in keeping with regional handwork techniques, and through partnerships with organizations like India's SEWA, the Self-Employed Women's Association.

As much a social thinker as an artist, Kim creates garments with artisans in places like Columbia, Oaxaca, Nigeria, and India. Her collections might feature fabrics from jamdani weavers in India or Yoruba cloth from Nigeria. Through these projects, she celebrates craft traditions, but more importantly, provides long-term, fairly waged work to people who need it. In this sense, Kim is a conduit between worlds, connecting the modern, global market with the traditional handwork of these peoples, allowing them a place where their work is honored, supported and in demand.

While other designers may capitalize on the skills of overseas workers through cheap labor, Kim approaches collaborations from a place of respect and compassion. Contrary to the usual bottom line of reducing supplies and labor to maximize profit, Kim purposely designs garments that require heavy handwork, thereby providing sustenance for her workers. It is a surprising, refreshing business model for the twenty-first century—one that not only maintains the work of the human hand, but upholds each person's right to proper livelihood, to lasting work that feeds their bodies but also their souls.

Collaborations are designed with a long-term vision. "If I decide to do a project with a group, it's important to keep a certain continuity for at least three years." Kim says. "I'm bringing new ideas, but also hope that they will have work. I feel my obligation is to support them for a few years so they can see how their life changed. Not only their creative outlet, but their actual economic outlook. It is easy as a designer to have a whim of an idea and go in, do that and leave—that isn't really in my background." This model allows for a certain familiarity with her workers too, creating a platform for an exchange of ideas. "They bring a lot to me," she continues. "Even when I see the way they sit, what they wear, what they think. It allows me to be a designer that's much more flexible and pliable. And you could only get that by spending time with them. Time is the one thing we can't buy. Initially, they look at you as a designer and are shy, and through time you can create a certain amount of equality, which is really important."

Given the labor-intensive nature of Kim's designs, recycling seems a natural progression. The more involved she became in production since Dosa began in 1984, the more she saw the waste created, despite her best efforts at being conscious. Launching the Dosa house wares line allowed her to find new uses for off-cuts and incorporate her interest in spaces, Bauhaus and Amish architecture. One of the first projects was a leather pouf, an ottoman-like item stuffed with leftover Polartec fleece fabrics (made of recycled plastic bottles).

Recycling also pops up in decorative ways that have become the company's signature. Remnant yarns from Kashmiri shawls are unraveled, re-spun and rewoven. Vintage handkerchiefs are repurposed into wrap skirts. Liberty cottons come together in gorgeous, patchwork blouses. Smaller fragments become bracelets, necklaces or appliqué embellishments on garments. Everything is used, down to the tiniest scraps. Even fabric is created from remnants, such as scraps of jamdani that are sorted, sometimes over-dyed, and then appliquéd into new, running yardage. "There's a lot of cooking with what's left over," Kim comments. "When you own a company, you really look at your design process differently. I work so closely with the artisans and I see the effort they put in to do what they do. One way to thank them is to utilize everything they make."

While gentler on the environment, large-scale recycling comes with added labor. Scraps that would be thrown away must now be sorted, bagged, weighed, and marked, then shelved, awaiting their new destiny—sometimes for years. As the sole designer—save what liberties her workers take in the creative process—Kim does much of it herself. “It’s really labor intensive, because in order for me to come up with a design I actually have to do the sorting. But I think that also gives a certain intrinsic value that is hard to measure.”

This value is a longstanding foundation of Dosa, which has built a reputation for being ecologically and ethically conscious long before it became trendy to do so. For Kim, recycling is not a passing fad, but a way of life rooted in her Korean childhood. "I am from a generation where I learned to do things differently," she says. "Growing up, our pillows, a lot of our clothing was made from leftovers. I find that's a comfortable place for me. I don't see it as anything different from how I grew up. It's a continuation of what I know; it's who I am."

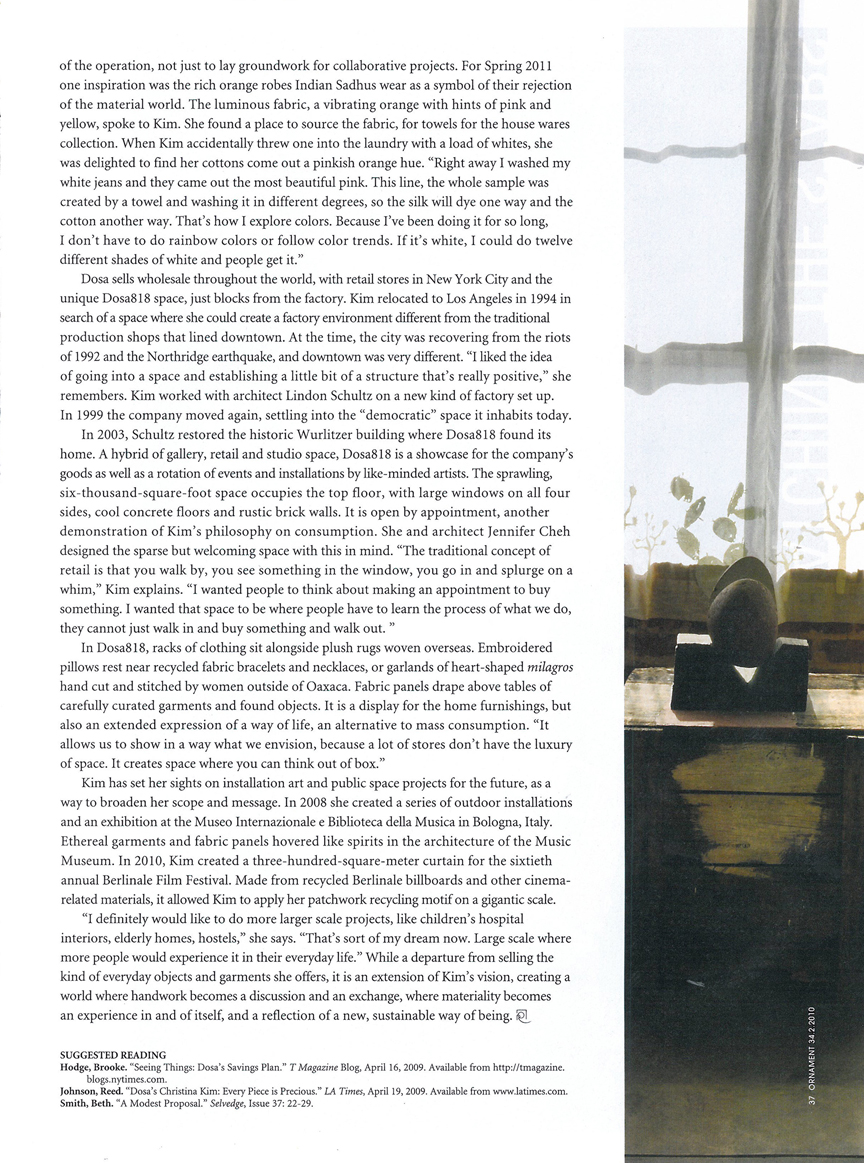

In addition to working hands-on with craftspeople, fabric is central to Kim's process. Her love of textiles is palpable, culminating in contemporary garments that carry a sense of memory within their threads. One of the key fabrics is khadi. "Khadi is an Indian word, it means handspun, handloomed," Kim says. "I use it loosely, anything handspun, handloomed is what I'm interested in. I'm trying to use as many hands as possible, so handspinning, handweaving creates an incredible amount of work that's time consuming. It also creates this patina of hand where you can really feel somebody's energy through it." Organic cottons are a staple, in poplin, canvas, muslin, linen, jersey, and other forms. Sheer charka and iridescent habutai silks, and African wax print cottons also show up. Results are multiplied by the way fabrics receive dyes. Beautiful indigo tones will vary from broadcloth khadi silk to an organic cotton/linen blend. The differences are subtle, lovely.

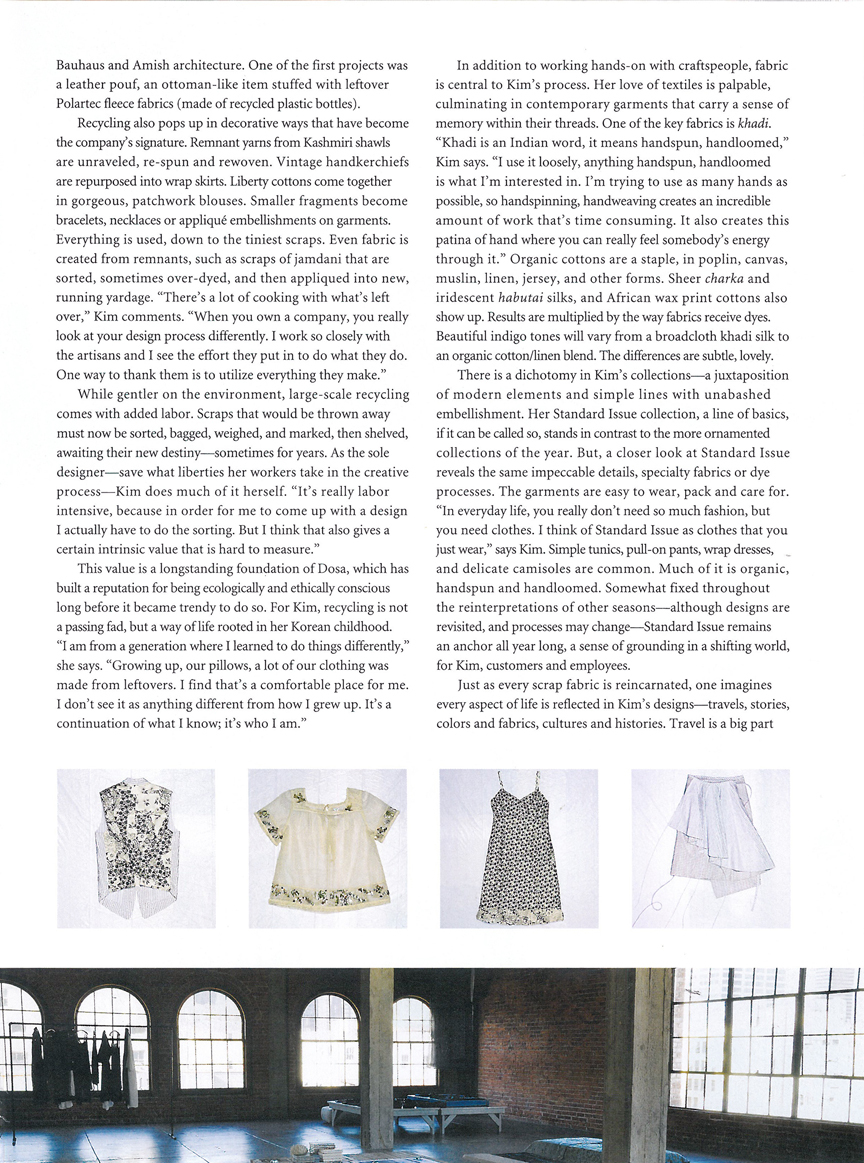

There is a dichotomy in Kim's collections—a juxtaposition of modern elements and simple lines with unabashed embellishment. Her Standard Issue collection, a line of basics, if it can be called so, stands in contrast to the more ornamented collections of the year. But, a closer look at Standard Issue reveals the same impeccable details, specialty fabrics or dye processes. The garments are easy to wear, pack and care for. "In everyday life, you really don't need so much fashion, but you need clothes. I think of Standard Issue as clothes that you just wear," says Kim. Simple tunics, pull-on pants, wrap dresses, and delicate camisoles are common. Much of it is organic, handspun and handloomed. Somewhat fixed throughout the reinterpretation of other seasons—although designs are revisited, and process may change—Standard Issue remains an anchor all year, a sense of grounding in a shifting world, for Kim, customers and employees.

Just as every scrap fabric is reincarnated, one imagines every aspect of life is reflected in Kim's designs—travels, stories, colors and fabrics, cultures and histories. Travel is a big part of the operation, not just to lay groundwork for collaborative projects. For Spring 2011 one inspiration was the rich orange robes Indian Sadhus wear as a symbol of their rejection of the material world. The luminous fabric, a vibrating orange with hints of pink and yellow, spoke to Kim. She found a place to source the fabric, for towels for the house wares collection. When Kim accidentally threw one into the laundry with a load of whites, she was delighted to find her cottons come out a pinkish orange hue. "Right away I washed my white jeans and they came out the most beautiful pink. This line, the whole sample was created by a towel and washing it in different degrees, so the silk will dye one way and cotton another way. That's how I explore colors. Because I've been doing it for so long, I don't have to do rainbow colors or follow color trends. If it's white, I could do twelve different shades of white and people get it."

Dosa sells wholesale throughout the world, with retail stores in New York City and the unique Dosa818 space, just blocks from the factory. Kim relocated to Los Angeles in 1994 in search of space where she could create a factory environment different from the traditional production shops that lined downtown. At the time, the city was recovering from the riots of 1992 and the Northridge earthquake, and downtown was different. "I liked the idea of going into a space and establishing a little bit of structure that's really positive," she remembers. Kim worked with architect Lindon Schultz on a new kind of factory set up. In 1999 the company moved again, settling into the "democratic" space it inhibits today.

In 2003, Schultz restored the historic Wurlitzer building where Dosa818 found its home. A hybrid of gallery, retail and studio space, Dosa818 is a showcase for the company's goods as well as a rotation of events and installations by like-minded artists. The sprawling, six-thousand-square-foot space occupies the top floor, with large windows on all four sides, cool concrete floors and rustic brick walls. It is open by appointment, another demonstration of Kim's philosophy on consumption. She and architect Jennifer Cheh designed the sparse but welcoming space with this in mind. "The traditional concept of retail is that you walk by, you see something in the window, you go in and splurge on a whim," Kim explains. "I wanted people to think about making an appointment to buy something. I wanted that space to be where people have to learn the process of what we do, they cannot just walk in and buy something and walk out."

In Dosa818, racks of clothing sit alongside plush rugs woven overseas. Embroidered pillows rest near recycled fabric bracelets and necklaces, or garlands of heart-shaped milagros hand cut and stitched by women outside of Oaxaca. Fabric panels drape above tables of carefully curated garments and found objects. It is a display for the home furnishings, but also an extended expression of a way of life, an alternative to mass consumption. "It allows us to show in a way what we envision, because a lot of stores don't have the luxury of space. It creates space where you can think out of box."

Kim has set her sights on installation art and public space projects for the future, as a way to broaden her scope and message. In 2008 she created a series of outdoor installations and an exhibition at the Museo Internazionale e Biblioteca della Musica in Bologna, Italy. Ethereal garments and fabrics panels hovered like spirits in the architecture of the Music Museum. In 2010, Kim created a three-hundred-square-meter curtain for the sixtieth annual Berlinale Film Festival. Made from recycled Berlinale billboards and other cinema-related materials, it allowed Kim to apply her patchwork recycling motif on a gigantic scale.