life of jamdani

life of jamdani

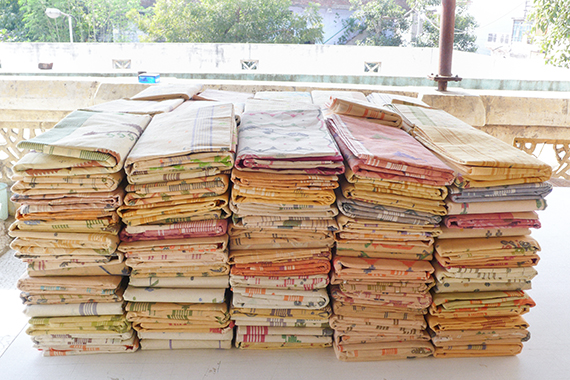

In 2002, I was invited by the National Institute of Design (NID) in Ahmedabad, India. They were soliciting designers and artists to go to Kutch and work with artisans in the earthquake-affected area. When I was in Ahmedabad, I went to a fair exhibiting saris from different parts of India. I was drawn to the West Bengal booth because of the interesting way they juxtaposed stacks of sari color. I was intrigued by the color palette, very different than the one I was used to. I walked over and started piling up the saris on the table and creating a new color palette for dosa. One of the NID design students present said, "I'm from West Bengal and I would love to do a thesis project for you" and so I sponsored her. She went to West Bengal and studied the history of jamdani as well as current jamdani production and this is how I began working with the cloth.

I started dosa with my mother in 1984, when I was living in New York. Back then, I wasn’t as involved in the day-to-day operations and production in Los Angeles, but was in the front line dealing with sales, talking with our customers. When I moved back to Los Angeles in 1996, I was at the factory every day and played a more active role in the operational side of the business. As an owner of a small design company, you end up taking the trash out at the end of the day. At this time, we were using a lot of recycled polar fleece and we were throwing out bags and bags of fleece scraps. I was already thinking about environmental issues and felt I was definitely a part of the problem and not the solution. So I sat down and really thought about how I wanted to produce; what does it mean to be a conscientious designer? Around this time we started saving scraps. In the beginning, we started making leather poufs stuffed with all the leftover polar fleece scrap. A simple shift in how we looked at our fabric usage resulted in reusing one hundred percent of the fabric. To date, we have made 1,400 poufs using the equivalent of 12,700 kilograms of fleece scraps or 24,190 meters for stuffing. The other large textile pieces that came out of our cutting room were made into shopping bags and used at our New York store. At this time, as a designer, I felt I was becoming conscientious about our impact and making a positive change.

My first trip to India was exactly 20 years ago in 1996 and that's when I began using handwoven textiles. I saw first hand the amount of time and effort it takes to make a handmade textile. Afterwards, I just couldn't justify throwing away any scraps, so we saved them. I didn't do much with them at the time, but it was a considered design decision to just start saving.

In 2008, I began designing with the following questions in mind: Is it organic? Is it recycled? Is it off the grid? Off the grid, at dosa, is defined as being handmade or handworked using human energy rather than by machine. Handmade being either handwoven or handknit. Handworked means that 20-30% of the garment has been transformed by an artisan’s hand via handstitching, woodblock printing, hand painting, embroidery, etc. By analyzing our 2015 data we have determined that on average 11% of our collection is organic; 7% utilizes recycling; 56% is handmade; 23% is handworked and 61% of the fabrics are designed by dosa. We use just about all the fabric that we bring into dosa.

The jamdani fabric we use is a traditional sari cloth from West Bengal woven in a pit loom. The pattern of the design, drawn on paper, is pinned beneath the warp threads and as the weaving proceeds the motifs are worked in, like embroidery. As the weft thread approaches the motif, the weaver takes up one of a set of bamboo needles, each of which is wrapped in different color yarn needed for the pattern of the motif. As every weft thread passes through the warp, the weaver sews down the intersected portion of the pattern with one of the set of the needles until the pattern is complete. Once the weaver established the rhythm they usually disregard the pattern and are free to improvise. I love the idea of the weaver having a certain amount of creative freedom. That's another reason I was interested in working with jamdani, because the weaver has as much creative input as the designer and therefore each 11 meter length of sari fabrics tend to be unique in color and design.

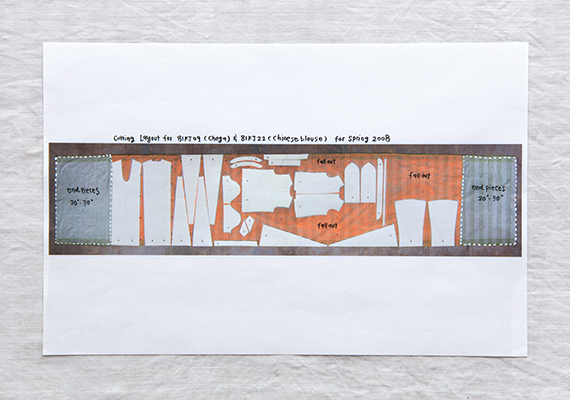

When I'm working on the shapes for the collection, I try not to be too concerned with recycling. There are a lot of indigenous shapes I'm interested in exploring partly because of the way the makers use the fabric. Since they tend to make their own fabric they want to maximize it when they cut it. I'm inspired by patterns that are engineered to fit the fabric, however I love the idea of recycling so much that I have loosened our cutting markers to allow for scrap. Our cutter laughs at me, because it's very unusual in the fashion industry to go from making a tight and “efficient” marker to a more relaxed one that generates “scraps.”

From 2002-2008, we purchased and used 12,210 meters of jamdani to produce 4,700 garment units. I saved 570 meters of jamdani endpieces and 155 kilograms of jamdani scrap from our clothing production. In order to reuse them, I took the scraps from West Bengal and brought them to Gujarat. My aim was to use an appliqué technique traditional to Rajastan and Gujarat to re-purpose the textiles. Bringing West Bengali fabric to Gujarti artisans made their work dynamic. They were delighted to handle this unique cloth rarely seen in this part of the country. That is also what made the recycling and repurposing so unique, precisely because you're introducing something new to a group of people used to doing appliqué in a very particular way.

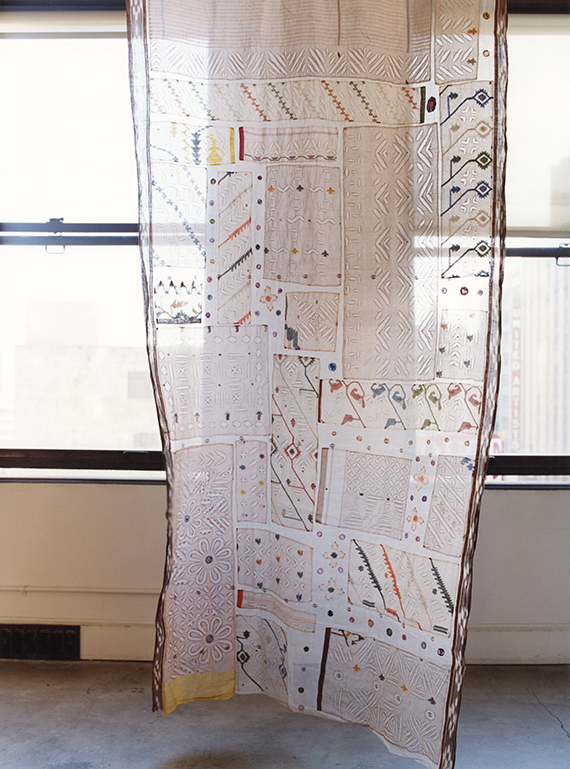

In order to organize all the scraps, I started with one big pile. At this point, the appliqué artisans weren't sure whether or not they should sort the scrap. In the Indian caste system, the people in the lowest caste are the ones who would sort the trash, or in this case scraps, so you could imagine that I was met with some resistance. I have worked in different countries and experienced people who follow different principles and traditions. Knowing this I jumped in and setting an example started sorting the scraps thus the making the process possible. I feel I redefined how they looked at this type of work. After sharing with them that my inspiration was the Tree of Life stone carved window from the Sidi Saiyyed Mosque in Ahmedabad, we starting working on a layout together. I gave scraps to each of the women and asked them to layout the fabrics. It was really interesting to see them create designs inspired by the patterns on the jamdani textiles using their own traditional Gujarat appliqué technique. Through this new process, they were given the freedom to be creative in their own familiar way yet be inspired by Bengali textiles. We made the very first sample and they were very satisfied with their work. In fact, they loved making it and they thought it was very beautiful.

At that point I had to establish a system in order to create textile panels four-meters long. This length was determined to be the most manageable for the artisans. The base was sewn together out of the end pieces of the saris, which were less ornamented. After I separated the scraps into color groups, we would lay them out on top of the base panels. Once it was laid out we basted the scraps to the panel. Then the women would draw the motifs with pencil, cut and reverse appliqué the designs. I'm interested in the layers of work, in keeping the memory of every gesture that we make. I told them, “don't worry about the pencil marks, keep the pencil marks because that is your design intention.” All this was very new to the artisans. I think it gave them a lot of self-confidence to be able to make decisions on their own. Once the system was in place, they were able to continue to make the panels, each being unique.

Some sari colors were off and some were sun-damaged. There was a dyer next door to the workshop I worked at in Ahmedabad, so we took all the scraps that didn't work and we had him dye them into a very dark shade of brown (ray). We laid it out using the same technique as the previous color (satyajit) thus creating two different color sets for this collection. Our first year recycling, using 88 kg of scrap from our 2002-2008, collections we made about 800 meters of re-engineered textiles. The panels were then sent to Los Angeles to produce garments. We made 108 Fraulein dresses in satyajit, 134 in ray, 85 eungie skirts in satyajit, and 82 skirts in ray; totaling 409 garments and 11 textile panels (4m in length.) Meanwhile, we continued to save the scraps from this recycled clothing collection from which we patched an additional 5 second generation recycled textile panels that averaged 3m x 4m. This production of 409 garments and 16 textile panels summed up to $113,910 in wholesale value. Thirty percent of the wholesale value went to the artisans while seventy percent was the total gross profit generated from this recycling project.

We had a lot of smaller pieces left after making the clothing and textile panels. When you looked at the pile of scraps the colors were so beautiful together. I wanted to utilize these pieces to create surface patterns using an applique technique known as tikdi, or small dot in Gujarati. Similar to a pointillist painting, individual colors are only one color but when you use repetition in variation you create a field of color. By using the small motif scraps we were also able to create texture. Varied colors allowed us to create several color groupings because of the way we sorted the scraps. Over 13 years we created seven styles that used recycled jamdani tikdi to produce 493 garments/accessories/textiles, including 354 tikdi shawls. Each shawl has 640 tikdi pieces coming from many different saris. In total we have used 277,424 individual tikdis.

After using the small scraps for tikdi production, we were able to find a use for event the tiniest of scraps. We made amulets each with a handwritten Hindu blessing inside. The making of amulets is a tradition in India, but because they were using beautiful West Bengal jamdani this gave them pleasure and knowing they were creating something out of nothing gave them a lot of self-satisfaction. As the head of a design and manufacturing company, I always think about how raw materials are utilized at dosa. How can we achieve zero waste? Throughout the entire recycling project we have worked with the same group of artisans and continue to do so.

I love working with my hands -- that's what gives me the most pleasure. And I love working with people. I enjoy communicating just with hands, drawings, and diagrams - without words. I think that gives lot of room for both the designer and the maker to be creative, because sometimes words are not adequate. The best part of my creative experience is done by learning their trade just by being with them, sitting with them and communicating through handwork.

I believe the key to being a good designer is to be able to produce things as well as you intended, better than original prototype. By learning and by spending time with artisans or the sewers, who are going to be the ones doing the production, you keep them thinking and keep them creative. Learn their trade, learn their skills, utilize their skills, and once you have developed a dialog between the two of you, trust them and see what you come up with together. It is truly a collaboration between maker and designer. It's respecting at every level, whatever that person or people are doing and creating. So much of work is so time consuming and as a designer, I don't think I spend as much time designing as the artisan spends time producing. I really value their time and I want to make sure it is well spent.

The process of recycling, sorting, documenting, cutting, patching and sewing all require manual time. Manual time equals more jobs, less additional natural resources. The investment to produce a recycled product is labor + time while a non-recycled product is material + labor + time. The recycled product means more pay going directly to the makers. From 2002-2014 we used 17,800 meters of jamdani fabric to produce 7,800 garments and textile panels. Of the 7,800 pieces, 87% were made from purchased yardage and 13% were made from recycled yardage. As we create more recycled units, we are able to increase our gross profits. From 2002-2008, 9% of our units were recycled and we generated an additional 17% in gross profits. 50% of the cost of our non-recycled production was fabric from 2003-2008, compared to 90% of the cost being associated with labor for recycled production. The money went to the makers we work with. Recycling generates additional profit and creates work for traditional craftsman.

I am as interested in sharing the design process as I am in the finished product. Similar to eating organic food, people need to know where goods come from and how they are made, this will help keep the artisan traditions alive. There is an intrinsic pleasure in wearing the handmade. You are supporting traditional craft and honoring natural resources.

photo: Raymond Meier, Gustavo Ten Hoever Palacios, Yoko Takahashi, Ku:nel